‘Play one of his records and you get an argument’

Ben Watson

‘I like Zapp, not Zappa – so please quit your jibba jabba’

Hot fucking Chip

One of the questions I dread being asked is ‘What kind of music do you like?’. As emergency exchanges of small talk go, it always makes my heart sink. The thought of listing random singers and bands makes me feel like if I’m back in the school playground, terrified of pledging allegiance to the wrong character in Whizzer and Chips, but replying ‘Oh, all sorts really’ is going to make me sound both dismissive and dull.

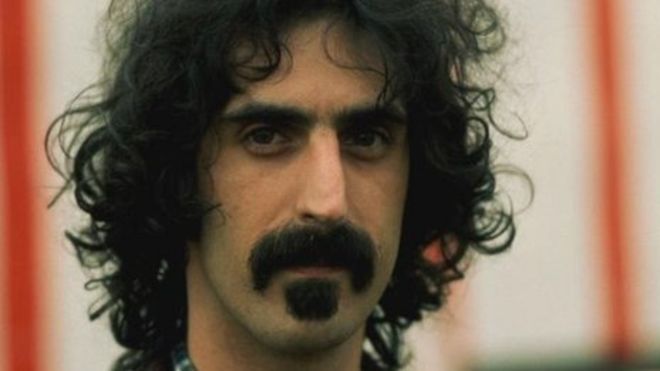

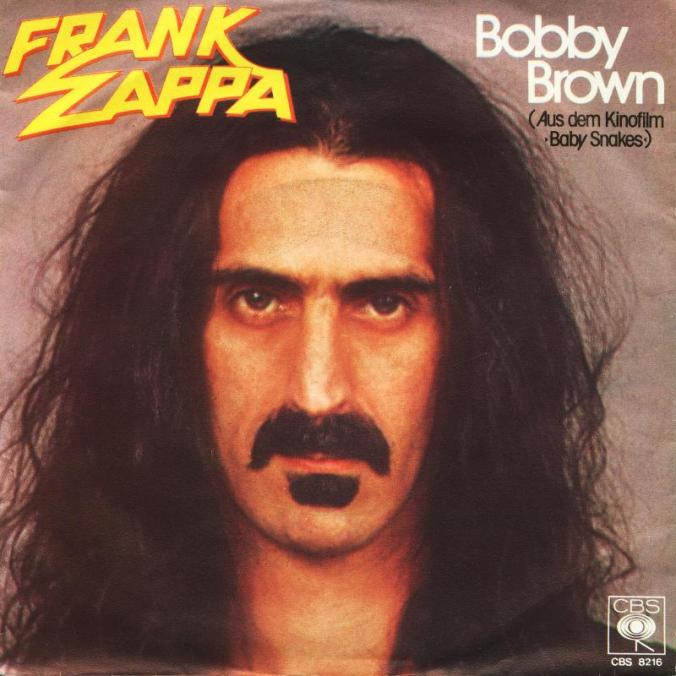

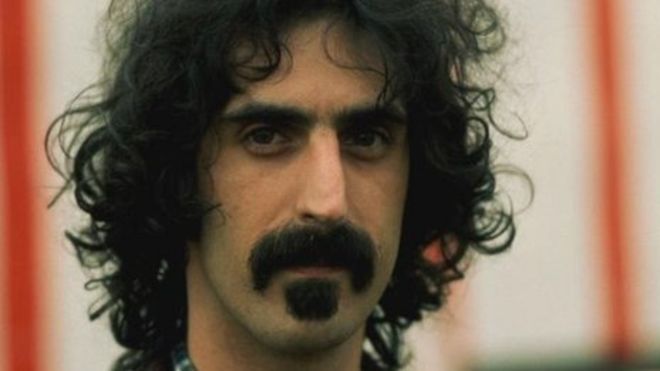

However, I’ve hit upon a perfect response, which is this: ‘All sorts really, but my favourite is probably Frank Zappa.’

Firstly, it’s true. Frank Zappa really is my favourite. He’s fabulous. If I could only listen to one artist’s music for the rest of my life, then without hesitation I’d make a beeline for his (admittedly gigantic) back catalogue. But it’s also the perfect answer because it brings the interrogation to a close: most people know Zappa’s name (which means the questioner’s satisfied, and there isn’t the ‘Sorry, who?!!?’ splutter you’d get if you said Einstürzende Neubauten or early Kleenex), but, because most people generally know pretty much nothing about him, the chat will have safely moved on to the weather in no time.

In fact, there are usually three basic responses you’ll hear upon dropping the Z-bomb in polite conversation:

- ‘He’s dead isn’t he?’

- ‘Crazy guy! Took loads of drugs! Haha. Didn’t he name his daughter Fridge Magnet?’

- ‘I’m more of a Captain Beefheart man myself.’

The first one is sadly true. The second is bollocks. The third means you’re probably talking to Johnny Cigarettes from the NME.

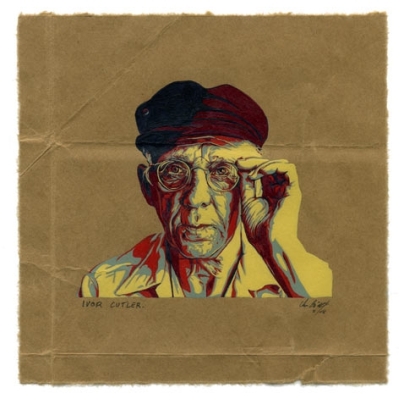

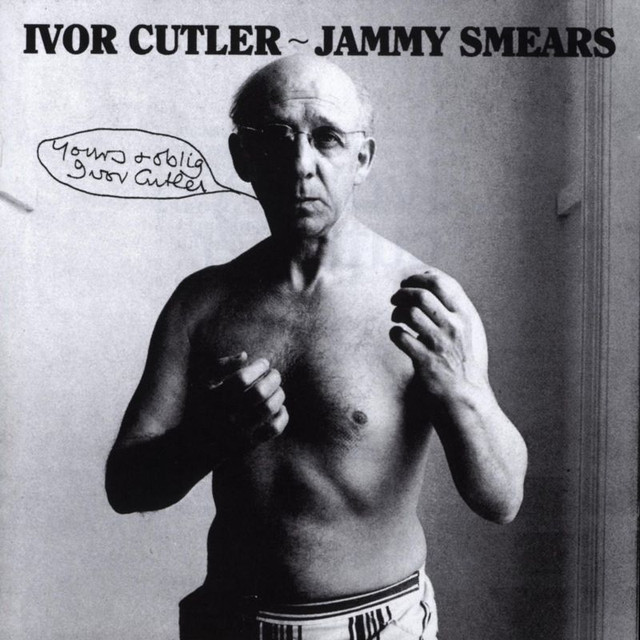

As ever, I’m not going to write The Definitive Frank Zappa Story here. It’s far too complex, and there are many books and documentaries out there. The best introduction to his music is undoubtedly Ben Watson’s Complete Guide, and for advanced students I can’t recommend his earlier tome The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play enough. I haven’t read Barry Miles’ biography, but I hear it’s refreshingly non-fawning. If you want to judge for yourself what Zappa himself was like, then going down a YouTube rabbit-hole of his TV appearances is a hugely enjoyable way to spend an afternoon.

What interests me is a simple question: why isn’t Frank Zappa better-known, and better-liked, than he is? Why don’t more people ‘get’ him?

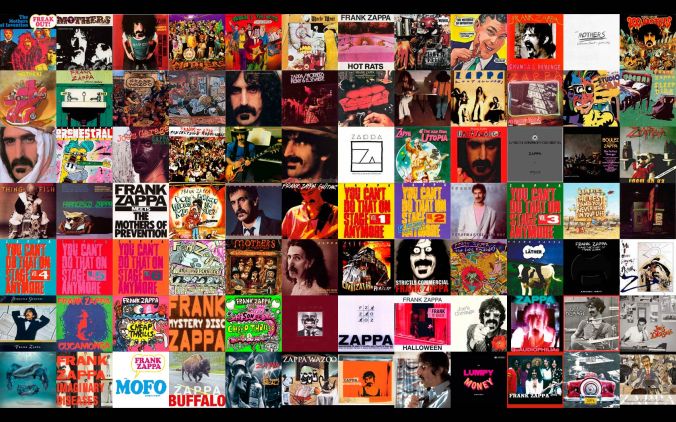

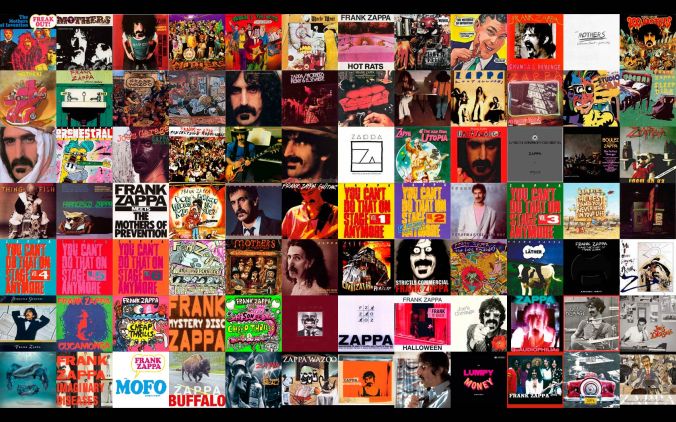

I ‘got’ Zappa almost immediately, when a friend of mine made me a cassette compilation. Compiling Zappa is a tricky endeavour: his catalogue is not only colossal (he put out 62 albums in his lifetime, and to date a further 47 collections from the archives have been released posthumously), it’s also wildly diverse in terms of genre. Official best ofs therefore tend to play it safe by discarding the jazz, orchestral, electronic and spoken-word stuff almost entirely and plonking the most radio-friendly rockers one after the other, perhaps with a token instrumental or ‘funny’ track at the end. His material is also hard to edit, both technically and conceptually – as with Monty Python, his albums use segues and thematic continuity in a way that really isn’t conducive to a greatest hits collection.

In contrast, my friend – who knew Zappa’s work backwards – suspected it was precisely these awkward aspects of Zappa I’d find appealing, and therefore thought there’d be little point in softening the edges. After all, if you’re going to be put off by strangeness, then Zappa isn’t going to be your thing anyway, so what would be the point? The tape was chronological, and I can still remember the brilliantly-edited opening sequence: Who Are the Brain Police?, Call Any Vegetable, Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance, Lumpy Gravy (‘Excerpt’!), Peaches En Regalia…halfway through side one, I was hooked.

You might be wondering why it’s been three months since the last blog post. It’s because, in preparation for this piece, I re-listened to his entire catalogue in order. And it’s been a joy. Some albums are of course better than others, but – astonishingly – there are no real stinkers. Every single one is different too, from the snorky silliness of the early Mothers material to the growling Gibson solos of the 70s belters, from his discordant dalliances with the London Symphony Orchestra to the concrète crispness of the Synclaviar years. But what’s interesting is that there isn’t really a career arc as such: pretty much everything Zappa came to create is all there on his 1966 debut Freak Out!, an expansively sprawling LP (a double, no less) which almost works as a mission statement:

You’re probably wondering why I’m here

And so am I, so am I

Just as much as you wonder ’bout me being in this place

That’s just how much I marvel at the lameness on your face

You rise each day the same old way

And join your friends out on the street

Spray your hair and think you’re neat

I think your life is incomplete

But maybe that’s not for me to say

They only pay me here to play

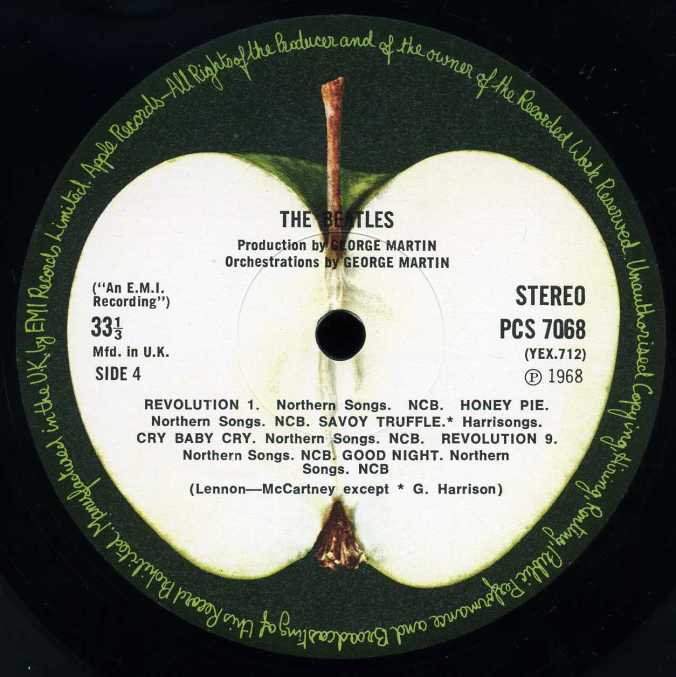

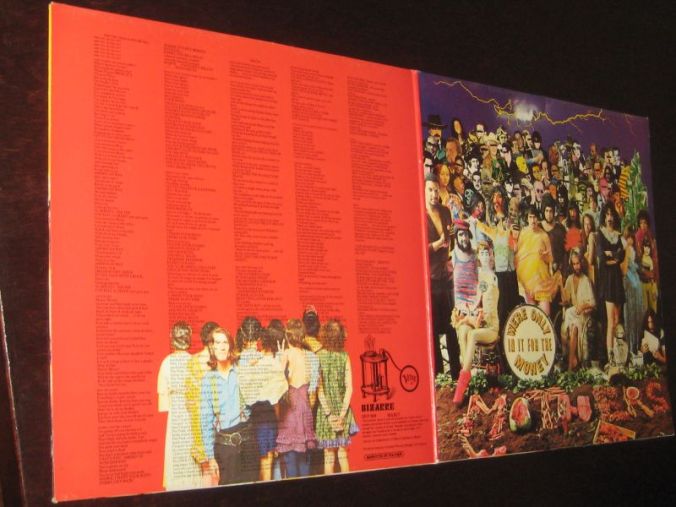

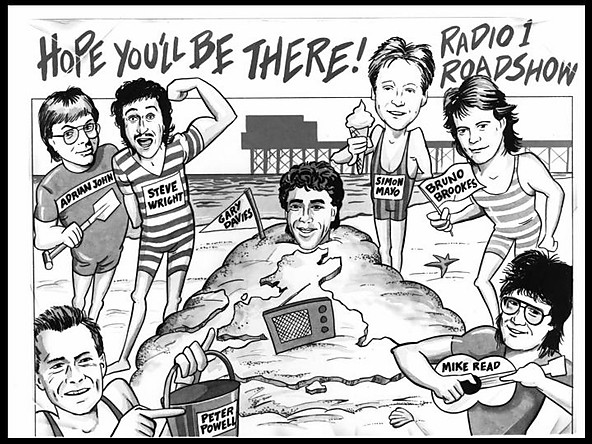

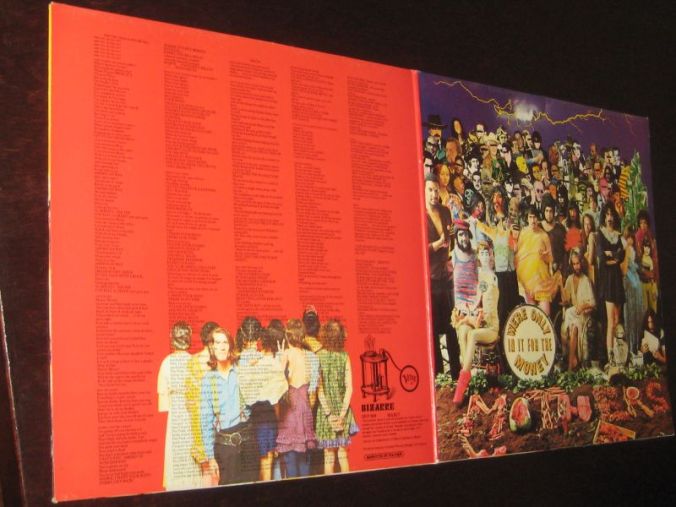

The first half of Freak Out! doesn’t frighten the horses, at least not immediately – a lot of it arguably wouldn’t sound out of place on a Nuggets-type compilation of garage-rock whimsy. Tony Blackburn could easily play Wowie Zowie or Any Way the Wind Blows on Sounds of the 60s and the Radio 2 switchboard would probably remain untroubled. There is, however, a ‘something’s not quite right’ feel to the songs, a sense that all is not well in Zappaland and things are about to get progressively stranger. Which indeed they do, and eventually we reach the insanity of Help I’m a Rock and It Can’t Happen Here, the latter pulling off a rare feat – that of being funny and frightening. Paul McCartney cited Freak Out! as an influence – initially on The Beatles’ still-unreleased creation Carnival of Light, and later on the Sgt Pepper album. There’s certainly more than a touch of The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet (the cacophonously bonkers ‘ballet’ which takes up the whole of side four) in the outro to Lovely Rita.

If I was to pick one of his albums, however, I think it’s his third release We’re Only In It For The Money where he got everything right. It’s almost a ‘best of Frank Zappa’ album, in the sense that it showcases everything that made him great: it’s satirical without being prescriptive or polemic; it pillories pop music while simultaneously celebrating its absurdities; it uses the recording studio as an instrument in itself; it’s funny, angry, political, baffling, unsettling, and – most importantly – it doesn’t skimp on the tunes.

I adore the way it pours scorn on the gormlessness of the hippy dream (‘I will love everyone, I will love the police as they kick the shit out of me on the street’) while at the same time offering something which was, even in 1968, sonically radical. I like the way it swerves in different directions, never staying in the same groove for too long – at one point almost literally so, as a snarling stylus deprives us of a sunny surf ditty. As soon as the listener starts thinking ‘Ah, they’re doing that kind of thing’, we’re immediately transported somewhere else entirely. ‘You think you know everything’ he sings on The Idiot Bastard Son, before immediately adding ‘Maybe so…’

But there’s so much to love in Zappaland, not least because he wrote complex and experimental music with a pop ear. Anyone can create bad avant garde noise, but he managed to create avant garde noise which was catchy. He also had the technical chops to create musical jokes and really make them land – the ‘Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers’ line from Baby Snakes is probably my all-time favourite Zappa goosebumps moment.

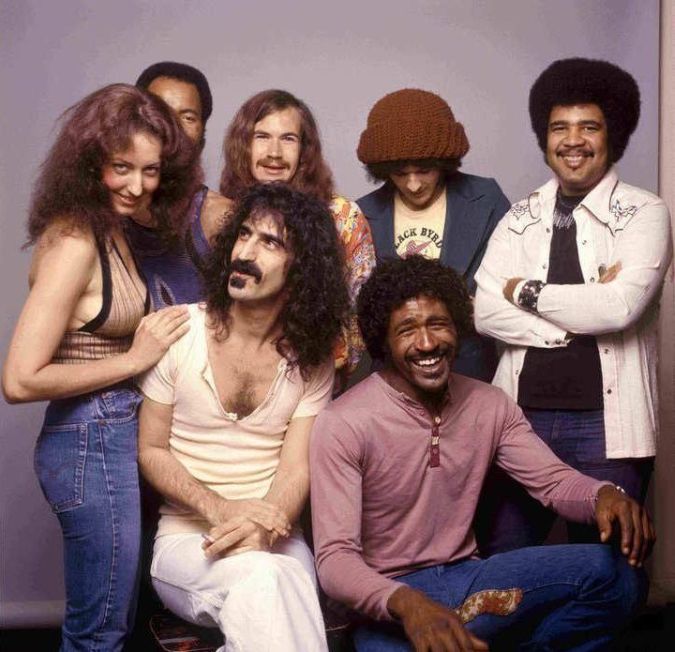

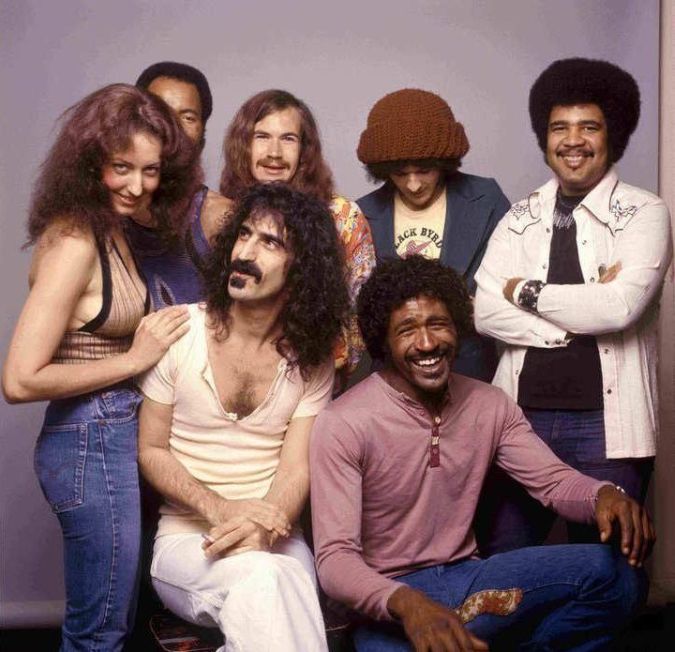

He also worked with so many extraordinary musicians. It’s hard to decide what I love more – the petulant bark of Motorhead Sherwood’s sax, the shiver and shake of Ruth Underwood’s marimba, the honeyed tonsils of the brilliant Ike Willis…they’re all incredible, mainly because they had to be. Zappa’s music isn’t easy to play. In fact, a lot of it’s hard even to hum. Try it with Peaches En Regalia right now. (You think you’ve got it, until you realise you’re doing the theme from Z Cars.)

There’s a stubborn, sometimes adolescent, cynicism in much of his work, but my re-listening project reminded me just how warm he could be too. For someone with clear disdain for the conventions and pretensions of the rock world, there was a part of him (quite a large part, I would venture) who was totally at home there. Watch footage of his concerts and you see a captivating showman, a stage entertainer every bit as good as Mick Jagger or Freddie Mercury. You can sense Zappa’s warmth in interviews too, where he’s endlessly patient in the face of the same terrible questions. He played the curmudgeon, but always with a reluctant twinkle in his eye

So…why don’t more people ‘get’ him? Assuming they’ve heard his music, I think there’s five basic reasons:

- He’s too weird

- The nose

- They haven’t heard enough

- The lyrics are ‘problematic’

- The fans

The first one is understandable enough – not everyone wants to be challenged by music, less still bludgeoned over the head by it. Music is to tap your feet to to, it’s to cheer yourself up, it’s to put on in the background while you descale the bath. Some people aren’t especially ‘into’ music, the same way I’m not especially into falconry or beach volleyball.

But what’s curious is that Zappa’s most prominent critics are often people with otherwise wildly eclectic musical tastes. Zappa doesn’t just divide people in the way you’d expect him to – he also divides weirdos. He divides people you’d think would like him. I’ve never been entirely sure whether this is because Zappa is simply too weird even for them, or because he’s weird in The Wrong Way.

Zappa worked in many genres, but he never really set up camp in any of them, which meant there was always an element of pastiche to whatever he did. So is it the apparent lack of ‘sincerity’ that people loathe? In their eyes, will he forever be (to use the phrase Zappa imagined critics might use for him) ‘the Ronald McDonald of the nouveau-abstruse’?

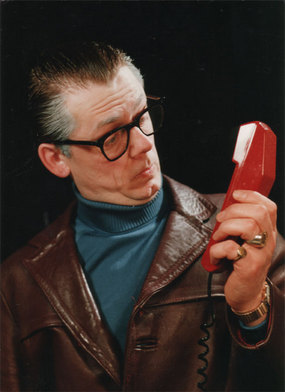

A track like Joe’s Garage should, you’d think, please anyone who likes 10cc or Steely Dan, yet it never turns up on ‘ultimate driving rock classics for dads’ type CD compilations. A piece like I’m the Slime should delight prog fans, and yet Rick Wakeman has yet to introduce it on Friday night BBC4. Perhaps we’re back to the ‘something’s not quite right’ factor, and this might explain why Tony Blackburn doesn’t play Freak Out!’s bubblegum piss-takes on Radio 2 – the listeners would somehow be able to detect the sneer.

Zappa’s work doesn’t just pull in different directions – it’s almost as if he relished a degree of self-sabotage. If he released a pop track, it would be in a fiendish time signature that was impossible to dance to; if he produced an orchestral work, he’d give it a rude name that people at the Proms would be too embarrassed to read out. There’s certainly a lot of ambiguity in his work – for example, I’ve never been able to work out how seriously the apparently earnest protest song Trouble Every Day is meant to be taken. In Zappaworld, nothing fits into neat boxes, and this is something that always annoys music critics – they want to know who someone is, and in which cabinet to file them. Maybe this is why so many people prefer Captain Beefheart – the wild and crazy guy they know how to label.

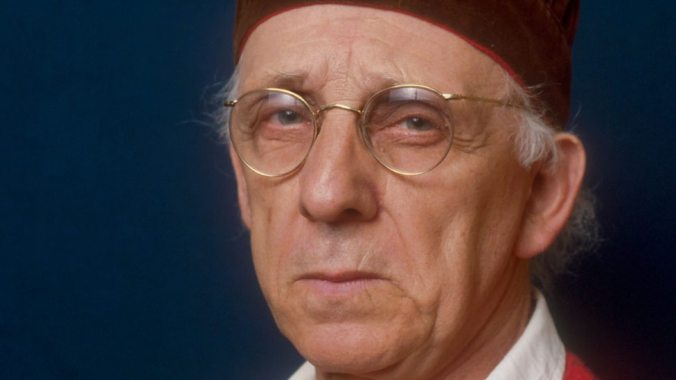

Stuart Maconie, who presents the BBC radio show The Freak Zone, is a big fan of ‘weird’ music but isn’t a big fan of Zappa. And this brings us onto point two. Asked what it was that bothered him about the great man, Maconie said it was mainly the nose. Or, more to the point, the fact that he was always looking down it: ‘He always had that look…one that seemed to be saying ‘I’m so much cleverer than you’.’

My immediate retort would be that, well, Zappa is cleverer than most of us…but I know what Maconie means, and I can understand why it might be off-putting. In Zappaland, Zappa himself is never the butt of the joke; he’s the cross dad at the disco; the man who drinks coffee at the LSD party, the guy at the love-in with a tape-recorder and a notepad. He’s a self-satisfied armchair sociologist who thinks his job is to ‘document’ and make fun of his inferiors. Everyone else is a buffoon, but not frowning Frank.

Well, that’s sort of true, and sort of not. We’re Only In It For The Money always strikes me as a record made by someone who not only fully accepts his contradictions and hypocrisies (ie, mocking a scene he was undeniably a part of) but also enthusiastically embraces them. He sneered at a lot of stuff, for sure (fer sure), but he also found a lot of his targets genuinely funny, and again I often infer a certain affection – most notably in the audio tour diaries, as laboriously curated on collections like You Can’t Do That On Stage Anymore and Playground Psychotics. In terms of ‘looking down on things’, though, one thing I do find disappointing with Zappa is his disdain for disco. Here, I always felt he fogeyishly missed the point of a scene which was, unlike flower power, genuinely revolutionary in terms of its racial and sexual politics.

To his credit, Maconie does still play Zappa’s music (nose and all) on The Freak Zone, and he’s probably the only person on the UK airwaves to be doing so.

Which bring us to point three. When people say they hate Frank Zappa, how much have they heard? And where on earth did they hear it?

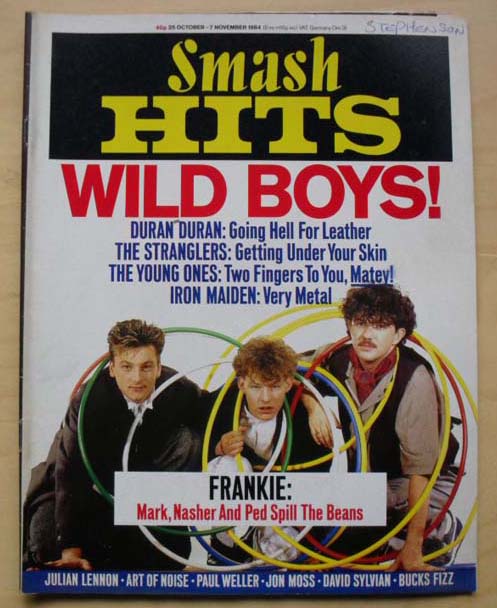

Zappa never had hit singles in the UK, although a few of his albums dented the charts. Zappa-haters often make an exception for Hot Rats, which made number 9 in February 1970, considering it to be his ‘only good’ album. I’ve never really understood why that is: it’s relatively conventional by Zappa standards, I guess, but only in the same sense that Waiting for Godot is Samuel Beckett’s poppiest play. My suspicion is that they make an exception for it because it’s the only one they’ve really listened to.

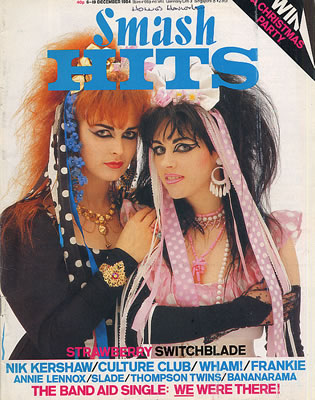

You see, I think Zappa-haters’ knowledge is generally based on a very small pool of tracks. Listen to a Zappa album on Spotify, and the ‘you might like this’ suggestions at the end are always the same ones: Dirty Love, San Ber’dino, Willie the Pimp, Bobby Brown Goes Down, Valley Girl, Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow. It never throws up selections from The Perfect Stranger or two minutes of Jimmy Carl Black complaining about cheese. When people say they hate Frank Zappa, what they probably mean is ‘I hate the seven Frank Zappa songs I’ve heard’. Which is fair enough (I’m the same with Adele), but I wish people were exposed to a bit more in the first place.

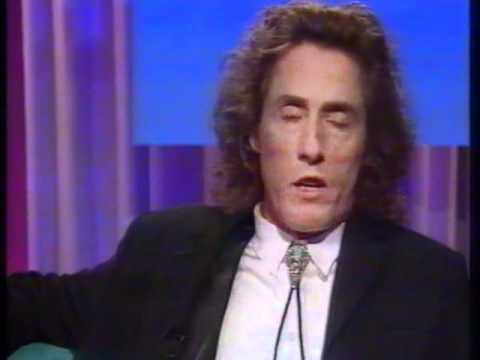

Freak Zone appearances aside, you don’t hear Zappa on the radio – and, in the UK at least, you never really did. Even John Peel appeared to be in the ‘I prefer Beefheart’ camp, although Andy Kershaw gave him a spin occasionally. If you hear a track, it’ll be on an unusual occasion – I remember Mark E Smith being a guest on Mark Radcliffe’s 6 Music show a few years ago and choosing Absolutely Free as his favourite record. Even on a station that tirelessly (and sometimes tiresomely) prides itself on its musical eclecticism, the track still had to be contextualised and set up as a special treat – it couldn’t simply be slipped in between Lust For Life and Making Plans for Nigel. I remember Nicky Campbell played a pleasing selection of tracks (including some relatively obscure cuts) when he interviewed Zappa in 1991, but this was partly because Zappa’s ‘difficulty’ was in itself under discussion.

Which brings us to point four. Oh dear. Put the kettle on, this might take a while.

Zappa’s approach to sex and race troubles a lot of people, and this is perhaps because the approach – once again – isn’t easily categorisable. He’s clearly no idiot, so his engagement with misogynistic and racist tropes and language must be satirical, right? You’d hope so. But again, we’re in Zappaland here.

In my younger days, I had what I thought was quite a good rebuttal to the charges against 1979’s Jewish Princess, a song which – on the face of it – appears indefensible:

I want a nasty little Jewish princess

With long phony nails and a hairdo that rinses

A horny little Jewish princess

With a garlic aroma that could level Tacoma

Lonely inside…well, she can swallow my pride

I need a hairy little Jewish princess

With a brand new nose

Who knows where it goes

I want a steamy little Jewish princess

With over-worked gums, who squeaks when she comes

I don’t want no troll…I just want a Yemenite hole

The offensiveness here seemed, even by Zappa’s standards, so brazenly outré (or in Nick Kent’s words, ‘feckless’) that I didn’t even entertain the idea that it wasn’t satirical. How could it not be? This was the guy who’d written the woke-tastic Thing Fish, for god’s sake.

So I looked at the song as it appears in context on the Sheik Yerbouti album, sequenced immediately after the terpsichorean tragedy Dancin’ Fool. Now Dancin’ Fool is sung in the first person, that of a lousy dancer (‘One of my legs is shorter than the other and both my feet’s too long’), and ends with the sad character in question chatting up a woman: ‘Wait a minute , I’ve got it, you’re an Italian! Huh? You’re Jewish? Oh, love your nails…’ Could it be, I wondered, that Jewish Princess is sung by the same ‘Fool’ character, and that Zappa was mocking the casual anti-semitism and misogyny of a lonely businessman – one who, failing to get anywhere on the dancefloor, might lie alone in his motel room and fantasise pathetically about ordering a sex worker on room service? One fact seemed to support this theory: Jewish Princess also followed Dancin’ Fool on the original live recording on which Sheik Yerbouti was based, and there is no record of it ever being re-performed in isolation.

It was a good hypothesis, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was trying to convince myself as much as anyone. Was I just making up excuses because I thought ‘with a garlic aroma that could level Tacoma’ was a brilliant line? (Which, you must admit, it is.)

Zappa’s own defence of the song was frustratingly ambiguous. ‘Unlike the unicorn, such creatures do exist,’ he told Spin magazine in 1991, ‘and deserve to be ‘commemorated’ with their own special opus.’ ‘I didn’t make up the idea of a Jewish princess,’ he told Playboy in 1993, ‘they exist, so I wrote a song about them. If they don’t like it, so what? Italians have princesses too.’ In The Real Frank Zappa Book, he related how he’d received fan mail from Jewish women saying ‘Finally there’s a song about me’. This was often his defence for such songs: it was ‘anthropology, pure and simple’.

In my younger days, I liked the fact that he refused to justify himself. As I got older I gradually found his response a bit glib and annoying, and I wished he’d clarified his position better. Was he crediting his audience with the intelligence not to have the satire spoonfed to them? Undoubtedly, but he was also using explosive topics for frisbee practice, and his irresponsibility bugged me. The ‘Ah, but actually he’s lampooning stupid white men’ defence has, of course, long been a cake-and-eat-it way of excusing all manner of grim fare.

During my re-listening process, I winced at his lyrics rather more than I would have liked, and Zappa doesn’t exactly make a defence (if you wish to make one) easy. After all, the ‘actually he’s lampooning stupid white men’ argument works perfectly well with his parody of Peter Frampton’s I’m In You, but seems rather tenuous when it comes to The Legend of the Illinois Enema Bandit; it works fine with Wet T-Shirt Nite, but not so well with Jumbo Go Away. The latter was one of the few tracks Ben Watson took exception to, eventually summoning up the courage to tackle Zappa on it directly:

Watson: Here’s a…yes, I’ll dare ask it: Was it necessary to be quite so cruel to Jumbo?

Zappa: Why?

Watson: It’s the only song of yours that really upsets me – because you talk about hitting her.

Zappa: Well I’m not the one who’s gonna hit her. That’s a true story.

Watson: That’s the reply I use to a lot of your songs to my friends. I say, ‘This is documentary of people’s behaviour.’

Zappa: Guy’s name is Denny Walley, it happened.

The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play, pp548-549

There’s something about Zappa’s reaction here that feels obtuse and disingenuous. He knows full-well what question is being asked but pretends not to; he knows that the mere truth of the incident is not what Watson’s objecting to; he knows that ‘it happened’ doesn’t always justify playing something for laughs. Even when Watson offers him an escape route, Zappa appears not to hear it.

One of Zappa’s most maddeningly ambiguous songs is also one of his most popular – the chart-topping (in Sweden and Norway at least) Bobby Brown Goes Down. On this, Zappa seems to delight in disorientating and winding up the listener:

Hey there people, I’m Bobby Brown

They say I’m the cutest boy in town

My car is fast, my teeth is shiney

I tell all the girls they can kiss my heinie

The nice liberal listener is tapping his toe so far…

Here I am at a famous school

I’m dressin’ sharp ‘n I’m actin’ cool

I got a cheerleader here wants to help with my paper

Let her do all the work and maybe later I’ll rape her

Woah, thinks the nice liberal listener. Hang on.

But before he has time to spit out his tea, we continue with:

Oh God I am the American dream

I do not think I’m too extreme

An’ I’m a handsome son of a bitch

I’m gonna get a good job and be real rich

The liberal listener breathes a sigh of relief. Phew, it’s OK, he thinks – it’s a satire on white America and toxic masculinity. I know where I am now.

But then he hears the rest of the song. And has to have a very confused lie-down.

Bobby Brown Goes Down can indeed be read as a satire on white America and toxic masculinity, and you can make an argument (with a totally straight face) that it’s a feminist piece. But it deliberately makes life difficult for you – almost line by line, the target of the satire seems to change, the same way a piece of music might change key. Bobby is clearly an unreliable narrator, much like the Fool in Jewish Princess.

Or is it just a thinking man’s rugby song? You decide.

The final objection might be why people find Zappa’s lyrics hard to stomach even if they accept the satirical intent: the bloody fans. It’s hard, after all, to argue that Bobby Brown Goes Down is ironic feminist satire when you’ve got 500 fratboys boorishly braying along to it. Indeed, a lot of Zappa-haters seem to cite a bad experience with a sycophantic fan as a contributing factor – someone who was convinced that everything Frank produced was unconditional genius.

Zappa fans can indeed be awful, the same way Python fans can be awful, the same way fans of anything can be awful. But most of them are perfectly lovely. In 1998, me and my friend (the one who made me the cassette compilation) went to see The Grandmothers – aka Jimmy Carl Black and Bunk Gardner – at the London Astoria, and it was a pleasingly idiot-free evening. In fact, I often find Zappa fans far more agreeable company than Zappa-haters. In my bookselling days I sometimes made compilations to play instore, and it was always gratifying to see how affectionately his stuff was received by the public. ‘Listen to the urgency of those trumpets!’ I remember someone remarking about Montana; it was so nice to hear someone actually talking about the music.

Zappa died in 1993, and inevitably I often wonder what kind of music he’d be producing today. The age of reality television, social media, the alt-right, Donald Trump, etc seems almost tailor-made for Zappa treatment, perhaps too much so. Would he think ‘That’s what everyone’s expecting me to do’ and instead do the total opposite? Who knows. I once had a horrible dream that Zappa came back from the dead and recorded a song about social justice and safe spaces called ‘Snowflakes’. (Thankfully I woke up before I heard it in full, although I remember he rhymed ‘problematic’ with ‘car’s an automatic’.)

What’s heartbreaking about Zappa’s death isn’t just that he’s no longer making music – it’s also that, despite spoiling us with endless material from the vaults, the Zappa family now appear to be split in two. This is largely (in fact, from what I can tell, entirely) because of a bizarre clause in his widow Gail’s will which gave ownership of the estate to Ahmet and Diva but not Moon and Dweezil. To this end, Dweezil has to ask his younger siblings’ permission in order to play his father’s music.

This is desperately sad, because – to echo Howard Stern’s words – I’ve always really liked those kids; I’ve always loved how funny and unscrewed up they seemed. The 1982 chat show appearances, when Frank and Moon were plugging Valley Girl, are some of my favourite TV moments of all time, and I’ve always found Dweezil’s commitment to keeping his father’s name and music alive incredibly touching. The ‘Zappa Family Trust’ now seems somewhat ironically-named.

So…why don’t more people ‘get’ Zappa? Perhaps the truth is that I don’t either. Not totally. But in a way, I quite like that. I enjoy the fact that I’m not fully in on the joke. I enjoy the fact that I don’t get all the references, and probably never will. I enjoy the fact that Zappaland is largely unsignposted. Maybe that’s (and this seems a suitably paradoxical note to end on) what makes me a Zappa fan.

Anyway. What kind of music do you like?