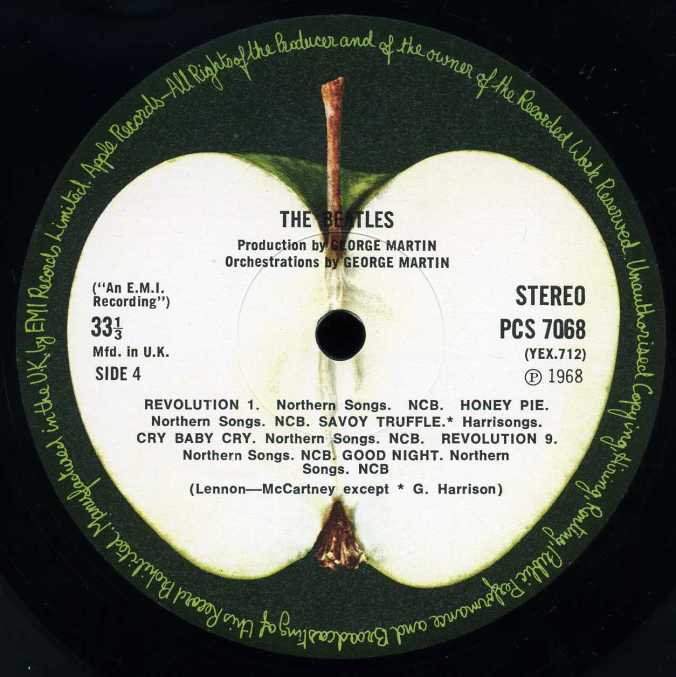

Something extraordinary happened 49 years ago. Thousands of children got a piece of avant-garde art for Christmas.

They didn’t know it, of course, and neither did their parents. They didn’t know it when they felt their stocking, they didn’t know it when they tore off the wrapping paper, and they didn’t know it when they eagerly placed it on the family Dansette. But as side four of The Beatles’ latest LP drew to a close, there it was: the ultimate uninvited guest. Some may have reached for the stylus in horror, many probably never played it again, a lot of dads no doubt said ‘Isn’t Billy Smart’s Circus on now?’…but they all heard it at least once. Never mind Molotov cocktails at the Sorbonne – including Revolution 9 on a number one pop album was the real revolutionary act of 1968.

The Beatles’ eponymous album, later colloquially known as ‘the White Album’, was a departure in all sorts of ways. How exactly do you follow Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, their game-changing chart-topping monolith from the previous year? Possibly by doing the complete opposite. In contrast to Pepper’s riot of colour, their new record bore an ‘anti-design’: an almost totally blank white sleeve, one where even The Beatles’ name was barely visible. The music itself was just as fulgent, but gone was Pepper’s intricacy and sheen – this was a looser, more ragged affair; bits of studio chatter weren’t always edited out, bum notes were left uncorrected, rough edges remained unsanded. Gone too was the sense of The Beatles as a harmonious quartet: it felt like (and on some tracks it genuinely was) four soloists performing separately under one fab umbrella.

The Beatles’ humour took a darker turn on the White Album too: from Lennon sneering at zealous lyric-combers on Glass Onion to McCartney’s Beach Boys pastiche in praise of the USSR, from Harrison’s scathing satire Piggies to Starr’s ‘you were in a car crash and you lost your hair’. The subject matter of the songs also involved a degree of misdirection: Julia is about Lennon’s mother, Martha My Dear is about McCartney’s sheepdog, Sexy Sadie is about the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and Blackbird is…probably just about a blackbird. But, strange though the individual songs are, what makes them stranger still are the sublime-to-the-ridiculous (and vice versa) juxtapositions; catchy singalongs are contrasted with more unsettling offerings, while heavier tracks are immediately followed by more soothing fare. The kid-friendly Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill swerves into the earnestly adult While My Guitar Gently Weeps, for example, while Long Long Long is very much the calm after Helter Skelter’s tinnitus-inducing tempest.

Revolution 9, however, is in counterpoint not only to everything else on the LP but to everything else in The Beatles’ catalogue. It’s an audio action painting; a sonic banquet groaning with sounds, some created and some scavenged; a swirling, twisting maelstrom of wow and flutter. Fragments of symphonies and choral motets jostle into one another like angry ghosts, while disembodied chatter and abrasive sound effects (crying babies, crackling fires, beeping car horns) crash in and out. Themes are constantly introduced and reintroduced, most notably a loop of a voice eerily reciting ‘Number nine, number nine, number nine…’

McCartney, who had co-designed the White Album’s cover, had been the member of the group most overtly interested in experimental music. In 1966, he was the Beatle with a copy of Frank Zappa’s Freak Out! under his arm and a ticket to a Cornelius Cardew concert in his pocket. Their (still-unreleased and still-unbootlegged) 1967 creation Carnival of Light, recorded for the Million Volt Light and Sound Rave at the Roundhouse, had largely been his baby, and he’d nominated Karlheinz Stockhausen’s face for inclusion on the Sgt Pepper cover montage. It’s ironic, then, that he had almost no involvement in Revolution 9, and later argued it should be withdrawn from the finished album.

The piece was primarily the work of Lennon (albeit with Yoko Ono as his backseat driver and Harrison as his game accomplice), who put it together while McCartney was on Apple business in New York. It’s unclear whether this was simply a case of Lennon being impatient with the idea and striking while his muse was hot, or if it was a deliberate attempt to steal McCartney’s ‘I’m the avant-garde one’ thunder. Probably a bit of both. ‘McCartney has, in recent years, made efforts to change the public image of him as the cosy domestic Beatle and of Lennon as the great radical experimenter,’ David Quantick notes in his book Revolution: The Making of the Beatles’ White Album. ‘He has a point. On the other hand, he didn’t make Revolution 9.’

Revolution 9 was not original. There had been tape collages before. In their podcast Something About The Beatles, Richard Buskin and Robert Rodriguez identify three specific compositions which foreshadow the piece: John Cage’s Williams Mix (1952), Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge (1955), and James Tenney’s Collage #1 (1961). Ian MacDonald in Revolution in the Head also suggests Stockhausen’s Hymnel (1967) may have been an influence. Their similarities to Revolution 9 are startling in some ways, but they also sound nothing like it; they feel somewhat self-aware and studied in a way that Revolution 9 never really does. Despite its nightmarish execution, there’s a freeness and naivety to The Beatles’ creation – it certainly doesn’t feel like an intellectual exercise for its own sake, and its use of collage (particularly the audio representation of violence and war) doesn’t feel crass or too on-the-nose.

Moreover, the sounds aren’t always what they seem – what’s often believed to be the sound of revolutionary chanting, for example, is actually an American football match (‘Block that kick! Hold that line!’), while the sinister voice intoning ‘Number nine…’ is from a Royal Academy of Music examination tape (to this day, the announcer has never been identified).

The whole piece, in fact, isn’t without Beatley jokes. The title itself is a pun, referring – like one of their earlier album titles – to a revolving record. It’s also, depending on whether or not you include McCartney’s ‘Can you take me back where I came from?’ link (and admittedly the CD gives this notion short shrift), nine minutes long, while the snippet of dialogue at the start, with a barely audible Alistair Taylor and George Martin talking about claret, lasts nine seconds. The White Album was also, in the UK at least, their ninth album; their ninth revolution.

Also in contrast to Cage and Stockhausen, it feels like a very personal – almost autobiographical – work, one that some see as very moving. Ian MacDonald talks about how the ‘wavelength-wandering radio-babble [resembles] the sound an infant might have apprehended in a suburban garden during a typical post-war summer’, and I think this is key to understanding – if not unlocking – what Revolution 9 is really about. Lennon himself recommended that people listen to Revolution 9 in the sunshine as well as the darkness: ‘See if you still think it’s about death then.’

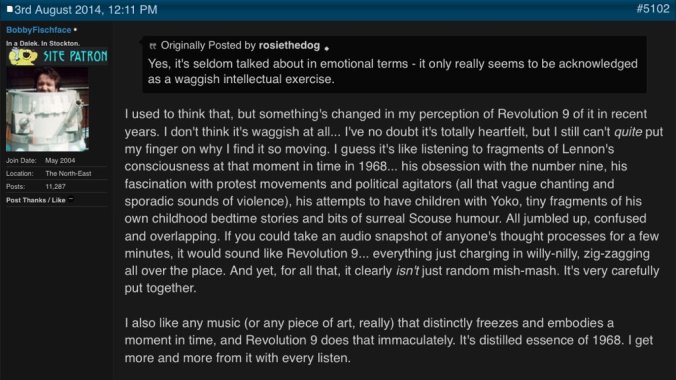

On the cult TV site Roobarb’s Forum, broadcaster Bob Fischer – whose show on BBC Radio Tees I heartily recommend, by the way – once wrote about Revolution 9 in these terms. With his permission, I’ve reproduced his fine summary here:

Revolution 9 used a long coda from Revolution 1 (the shuffly ‘unplugged’ jam which would later be rocked up and re-recorded for Hey Jude’s b-side) as its template; Revolution 9 was shaped like papier-mâché around Revolution 1 until most of the latter was unidentifiable or obscured. As such, it isn’t simply a whimsical assemblage of random noise – as Fischer identifies, it has a definite shape and structure, and a lot of thought has clearly gone into the positioning of the various elements. It’s hard to tell how ‘storyboarded’ the piece is, although Ruskin and Rodriguez note how Lennon, as the auteur of the piece, almost seems to be adopting a movie director role; he steers the action and selects the shots just as McCartney had done on Penny Lane.

People sometimes quip ‘How can you tell when avant-garde art is bad?’, and ‘the absence of structure’ is as good an answer as any. Lennon and Yoko’s Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins (released one week after the White Album) is, to me, an example of poor avant-garde art because the cacophony is not being configured in an interesting or inventive way. Revolution 9, in contrast, feels sculpted, the same way Love Me Do was sculpted.

Despite this, Revolution 9 is probably the most loathed track in The Beatles’ catalogue. Even those who call themselves massive Beatles fans (inevitably the same types of people who roll their eyes at the use of sampling on hip hop records) often boast of skipping it, or moan that the band could have substituted two or three Proper Songs in its place. A perennial topic on Beatle forums is ‘How would you edit the White Album down to a single disc?’, and Revolution 9 is the inevitable omission from nearly everyone’s fantasy tracklists. When Beatles fans discovered the album wouldn’t quite fit onto a C90, most of them didn’t have to think too hard about which track they could happily live without.

It would be faux-naif to ask why Revolution 9 isn’t a karaoke favourite, but what’s always puzzled me is why people who love previous examples of Beatles weirdness hate it so much. The obvious answer is that the likes of Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds and I Am the Walrus are, despite their oddity, still banging tunes. You can still sing along; Britpop bands can do cover versions for Mojo magazine; French clowns can adapt them for dance routines. Revolution 9 ‘simply doesn’t belong’ on a Beatles album is the usual argument – put it on Two Virgins, fine, but Beatles albums should contain Actual Music. ‘It’s like finding a lobster in your Quality Street’ I remember one person saying.

But The Beatles had been putting lobsters in our Quality Street for a long time. For those under the age of 60, it’s near-impossible to imagine just how radical Love Me Do felt in 1962; how raspy and raw it must have sounded; how rudely it must have cut through the easy-listening fug of the time. It’s also forgotten now that She Loves You was subtly original in pop terms simply because it was sung in the third person. There was the feedback at the start of I Feel Fine, the fade-in at the start of Eight Days a Week, the sitar on Norwegian Wood, and later there was the use of tape loops on Tomorrow Never Knows and Being For the Benefit of Mr Kite!, the fake ending on Strawberry Fields Forever, and the terrifying orchestra-orgasms on A Day in the Life. They weren’t the first musicians to do these things, but they were the first to really make them work within a mainstream pop idiom. Revolution 9 was simply the logical extension of what they’d always done; it would have been a step backwards to not do it.

Revolution 9 may not be recognisable as a pop song, but it’s still on a pop album. And there lies its genius. It’s one thing to perform avant-garde music before a self-selecting crowd of chin-strokers, but quite another to top the charts with it.

I sometimes get concerned that The Beatles’ legacy is being ‘de-weirded’. Their studio innovations seem to be played down, with the group gradually being rebranded as ‘just a great rock ‘n’ roll band’ whose ‘classic songs will live forever’. Conceivably one of the reasons for Carnival of Light’s continued non-appearance may be that it simply doesn’t fit in with this narrative – a narrative reinforced, in everything from the Rock Band video game to the Eight Days a Week documentary and the Hollywood Bowl reissue, that solid songwriting and musical chops are what really matter. Even the 50th anniversary remix of Sgt Pepper seemed to stress how much of the album was played live, while the eventual release of the Let It Be film will no doubt focus on how they could ‘really play’ up on that rooftop. 49 years after children unwrapped Revolution 9 for Christmas, what do we have now? Elbow covering Golden Slumbers.

So next time you play the White Album, don’t skip Revolution 9. Turn it up. In fact, play it nine times in a row. Right now, there’s too much Quality Street in the world and not enough lobster.