I’m at a pub quiz. Me and my colleagues from work, Quiz Team Aguilera, are doing pretty well. Between us, we have a lot of bases covered: geography, football, varieties of lettuce, the names for the different parts of a dolphin. But now it’s the entertainment round, and my buttocks are suitably clenched.

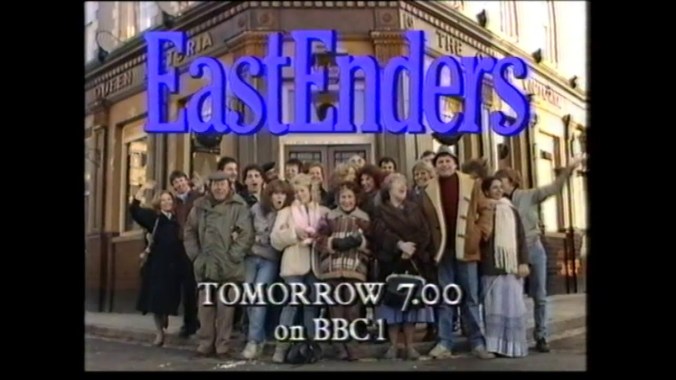

‘Question one,’ booms the host, leaning on a box of crisps. ‘In what year was EastEnders first broadcast?’

Cue muttering and furrowed brows from every team, including mine. ‘Hmm, it was 1980s wasn’t it?’ says one. ‘Yeah, definitely 80s. About…1987?’ replies another. I let a suitable number of seconds tick by before piping up:

‘It was 1985 I think.’

Thankfully there’s no further quibbling and 1985 goes on the paper, securing us the point. But inside I cringe at myself for adding that little cowardly qualifier: why did I feel the need to say ‘I think’ afterwards?

Not only did I know full-well it was 1985, I also knew the exact transmission date: February the 19th. Not only that, but I knew it was originally meant to start a month earlier. I also knew the date when it was re-scheduled from 7pm to 7:30pm. I knew the dates of the initial recording block and the date the first set of promotional photographs were taken on the set at Elstree. I also knew that one of them featured Jean Fennell, who was originally cast to play Angie Watts before Anita Dobson got the role. I knew that one of its original working titles was Square Dance. I also knew that, when you write the word EastEnders, the official style guide stipulates you must always capitalise the second E.

And the thing is…I hate EastEnders.

My team-mates were, of course, highly knowledgeable. They knew that Billy Bonds made his League debut for Charlton Athletic, and they knew that summercrisp lettuces have larger leaves than butterhead ones. They also knew that the middle bit of a dolphin’s tail is called the median notch. But that’s fine: that’s healthy, ooh-it’s-on-the-tip-of-my-tongue trivia. Stuff that can be cheerily laughed off as ‘useless information’. But knowing obscure stuff about a TV show you don’t even like? Knowing the dates? That’s just weird.

Most of my non-work friends are experts in ‘wrong’ things. They know what is commonly denounced as Far Too Much about pop culture, and they know it on a scale most folk would find decidedly odd. Whether it’s Candy Flip’s discography, the aspect ratios of WC Fields shorts or the logos for different brands of knock-off Baileys, they’re the people to ask. Two of them wrote a 600-page book itemising and cross-referencing every single sketch from the Radio 4 satire show Week Ending, a project so brilliantly insane in its ambition and scholarship that I strongly believe it should be the third compulsory tome on Desert Island Discs.

I’m always incredibly comfortable in their company because we respect and celebrate one another’s obsessions; we concede how ridiculous our interests might be, but we never deny or play down the passion that drives them. And unless we’re genuinely uncertain about something, there is never a need for a nervous ‘I think’.

But you can’t always hang out with those people. A lot of the time you have to mingle with, to use the word Hollywood actors apparently employ for those who don’t work in the biz, ‘civilians’. Normal people, with (gulp) normal interests.

I’m very awkward among civilians, particularly when pop culture subjects come up, because I don’t know the rules of their game. When a civilian asks ‘Have you seen any good films lately?’, are they expecting me to pick from a shortlist of approved Netflix fare, or can I be truthful and say ‘I’m really looking forward to the Blu-ray of Otley’? Sometimes, when civilians visit my flat, I sense their bafflement at the teetering towers of what can only be described as ‘physical media’ cluttering my coffee table. It would probably be more socially acceptable to collect Nazi memorabilia.

It’s not that civilians hate geeks – it’s that, within civilian circles, there are acceptable types of geekery. Sport is obviously fine. Cars? Also OK. A performative love of books? Almost mandatory. Cooking? Fill your geeky boots. Below that, there are types of geekery which are partially tolerated because they’re recognised eccentricities: civilians know what a ‘record collector’ or a ‘Star Wars fan’ is, even if they might roll their eyes at the notion; they’re ‘standard nerds’, to quote the term Denholm Reynholm uses for Roy and Moss in The IT Crowd. Geekdom is tolerated, but it has to be palatable or at least apologised for with an ‘I’m afraid I’m a bit of an anorak’ disclaimer.

Comic Book Guy in The Simpsons rings true with civilians because he ticks all the stereotypical boxes: arrogant, quarrelsome, unattractive, boring. A more nuanced or sympathetic portrayal of geekdom would just require too many footnotes. Characters in dramas (especially soaps, including 1985 favourite EastEnders) rarely have any interests in audio-visual media, except in the most generic sense possible – there’s just no time. If Ian Beale was seen encoding a VHS copy of Reggie Bosanquet’s Private Spy, imagine the back-story required to explain it.

There are also boundaries in terms of genre. A civilian will tolerate a Harry Potter fanatic having their photograph taken at King’s Cross station (they may even have done so themselves), but they’re going to eye me very suspiciously if I tell them I get equally excited about the spaghetti house from Yoko Ono’s Rape.

Tim Bisley, Simon Pegg’s character in Spaced, is a good example of the unthreatening ‘everyman geek’; the nerd who isn’t really a nerd. He likes science fiction and cult movies, but in a framed-poster-on-the-wall, being-able-to-quote-the-dialogue way. He’s a big fan of Blade Runner, yes, but he’s not going to contact the Ridley Scott archive and ask to look at the camera floorplans. He’s so mainstream he probably watches ‘making of’ DVD featurettes without freeze-framing the clapperboards.

When it comes to pop culture, the bar for being a ‘massive fan’ of something is generally very low. If someone says they’re a ‘massive Monty Python fan’, for example, that usually means they’ve seen Life of Brian twice. This is true even with people who present themselves as uber-geeks and appear to embrace esoteric info with fervour. I remember listening to Adam Buxton interviewing Michael Palin and gradually becoming dismayed by the obvious limitations of his Python knowledge: ‘Stop asking him about the bloody films’ I kept thinking, ‘Ask him about Mortuary Hour rehearsal sessions, or the strange dialogue at the start of Decomposing Composers.’ To most listeners, however, the chat was no doubt more than trainspottery enough.

Even with science fiction monoliths, there are unspoken rules about the kind of geekery that’s acceptable. I got blank looks from Doctor Who fans recently when I asked why the 3-disc Shada boxset only contains 45 minutes of studio rushes rather than several hours of it. ‘Why would anyone be interested in sitting through that?’ the fans replied. I wouldn’t mind, but these are the same people who write long blogs discussing the fluting on the Tardis windows.

But maybe this is the nature of geekery. It’s not a linear spectrum from normal to weird, but a complex collection of overlapping and intersecting knowledge-pockets, each with their own boundaries and rules of social acceptability. Some info can be laughed off in an I-think-I-heard-it-on-QI type way, while others are just too niche for comfort.

Something else to mention about the pub quiz: I might have known the start-date of EastEnders, but I was also under the erroneous impression that ‘Quiz Team Aguilera’ was a brilliantly witty pun that my colleague had coined on the spot. I only found out later that it’s a standard pub quiz name and about as original as naming your dog Fido. Everyone in the room knew this except me. So who was the geek there and who was the civilian? On different levels, we were probably each playing both roles.

I think.