(Content warning: Contains descriptions of medical treatment/experiences, including circumcision, that some may not wish to read.)

‘It’s like bedlam in here. Old men keep falling out of bed.’

Adrian Mole

My first visit to hospital was in 1979. I had a dodgy mole on my foot requiring swift removal, and Leicester Royal Infirmary was charged with the task.

Being five years old, my memories are inevitably hazy. I remember arriving at the battleship-grey ward and being shown to a crisp-white bed. I remember my parents presenting me with a box of multi-coloured Kleenex, the sobriety of the occasion justifying a degree of modest luxury. I remember granny smith apples and orange squash being placed by my bedside, and I remember them both being confiscated by the sister so they could be ‘shared out fairly’ (which they never were). I remember the plastic bracelet with my name on, and I remember thinking it would be a good idea if people wore them in normal life. But mainly I remember the fish pie.

You see, I didn’t like fish. I was what they used to call a ‘fussy eater’, and fish in particular freaked me out. Sadly for me, I’d arrived on a Friday, and Friday meant fish – buried under potato, admittedly, but fish all the same. Worse, the pie in question was billed as a special treat, one my wardmates were visibly looking forward to – I think some of them were even banging their cutlery against the table in anticipation. It’s alright, I consoled myself – mum and dad will explain to the nurses that I don’t like fish. It’ll be fine.

But no. Mum and dad had, with an apologetic wave, fucked off. The visiting time bell had tolled, to be replaced by the clank and squeak of a stainless steel food trolley. Portions of pie were duly scooped out and everyone except me enthusiastically tucked in. I didn’t consciously know it, as I gingerly poked at the least fishiest lumps of mash I could find, but this was an early lesson that certain things – not least my parents – wouldn’t always be there.

Later that afternoon, anxiety got the better of me and I voided my bladder rather spectacularly. I went puce with shame, but remember being shocked that the nurse didn’t seem remotely surprised or disgusted. ‘Ah, Michael’s had an accident! We all have accidents!’ she smiled breezily, reaching for the mop.

If fish pie wasn’t to my infant taste, surely the notion of a general anaesthetic should have posed an even greater threat? Oddly, I wasn’t especially troubled by this, or at least I don’t remember being so. What I do remember was the slightly odd non-sequitur between me and the anaesthetist as he prepared the syringe:

‘Have you ever been scratched by a cat?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ I replied proudly. I had once tormented my grandparents’ tabby by repeatedly yelling ‘MIAOW!’ sarcastically into her face. After about half an hour of this, the tabby (understandably enough) chose to issue a final written warning.

‘No?’ replied the surgeon. ‘Well, it feels a bit like this.’

Pure Samuel Beckett. Although it was another early life lesson – namely, that people in authority often aren’t listening to you. Especially when you’re talking about cats.

A few weeks later, a nurse came to our house and removed the stitches. My mother put them in an envelope and wrote ‘Stitches from Michael’s foot, 1979’ on the side, like it was a jar of marmalade.

My second hospital visit was in 1980, where an onset of phimosis (look it up – in fact, don’t, at least not at work) had necessitated a particularly unkind cut. I was old enough to be worried, but thankfully too young to really anticipate the full horror.

Circumcision for medical reasons is pretty common in children, but at the age of six I obviously didn’t know this. Something told me it was a rude operation, a shameful procedure that I should keep very very secret indeed. A ‘naughty complaint’, to use Graham Chapman’s phrase. I think I wisely told my schoolfriends I was having my tonsils out.

No such angst from the hospital staff, of course, who had seen it all before. Gallows humour was the order of the day. ‘Don’t worry, you won’t miss it’ I remember a doctor reassuring me, ‘although if you do, I’m sure your mother can knit you a new one.’ I remember waking up one morning to discover the latest joke by the nurses: my teddy bear Derek now bore two steri-strips over his groin in a comedy cross.

On the first night, my parents were bustled out of the ward abruptly, just as they had been before fishpiegate. Before I had time for the confused tears to well up, a consultant sauntered in, barked at a young nurse to draw the heavy turquoise curtains, and ordered me to lie on the bed and lower my pyjama bottoms. Petrified, I did as I was told.

As the nurse held up my doomed penis for inspection and the consultant furiously scribbled away on a clipboard, I screamed and sobbed, a display both of them seemed to find ludicrous. ‘Anyone would think I was doing the operation now!’ he joked, and the nurse (without loosening her grip) giggled. I would have joined in their laughter, had that not been exactly what I was thinking.

I don’t remember much about the operation itself, except that the porter whistled the theme to Only When I Laugh as he wheeled me into theatre. You might remember the disturbing lyrics to this tune, as mournfully intoned to the accompaniment of a Somme-style harmonica:

I’m H-A-P-P-Y

I’m H-A-P-P-Y

I know I am, I’m sure I am

I’m H-A-P-P-Y

‘Do you watch that show?’ he asked. ‘Funny isn’t it?’

I nodded sleepily. I didn’t feel much like Peter Bowles at that point, although I had to admit I was jealous of his dressing gown.

I remember more about the day afterwards, when I was forced to take a bath under the supervision of a student nurse. ‘Ooh look…there’s the blood!’ she helpfully informed me at one point, gesturing towards the vermilion clouds now billowing between my legs. (Thankfully at this point the porter didn’t come in and say ‘Have you seen Carrie? Funny isn’t it?’.) This experience naturally unsettled me, and I didn’t dare peek at the handiwork in question for weeks.

The third operation in 1981 was the best because…well, it didn’t happen. I was inducted as usual and given my plastic bracelet. My granny smiths and orange squash were once again carefully arranged by my bedside (and once again later confiscated), and I spent the night listening to the rattle of a nearby radiator – a comforting sound I always associated with municipal buildings. But my operation – this time to correct hearing problems – was cancelled. Hooray, I could go home. The only downside was that I had a crush on the patient next to me, a girl with an impressively-autographed cast on her tractioned leg. I remember telling her the fish pie story and she expressed solidarity by theatrically sticking her fingers down her throat. I was slightly sad to leave her side.

The real upside to the 1981 visit was that my parents had bought me loads of post-op presents, ones I obviously didn’t deserve but got to open anyway. These presents included a chemistry set, a piece of Lego spaceware (a shovel buggy I believe) and a copy of Joe Dolce’s then-current hit Shaddap You Face. The latter is a record which, to this day, never fails to make me happy (and indeed H-A-P-P-Y).

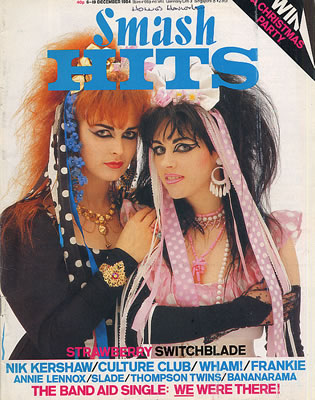

My fourth visit was in December 1984, a week or so after the Band Aid single was recorded. I know this because Strawberry Switchblade were on the cover of Smash Hits – a decision editor Mark Ellen now cringes at, but I think he made exactly the right call. The calming presence of Jill and Rose certainly got me through the first night anyway.

This time I was to have my tonsils out, and thankfully my friends had forgotten the white lie I’d told them four years earlier. I was furious when I found out the date, because it meant I missed out on an unimaginably exciting school outing – namely, a trip to see Ghostbusters. Bah!

I was listening to Gary Davies on Radio 1 playing Queen’s Thank God It’s Christmas when the porters arrived for me. Rather discourteously, they had arrived just as he was about to announce the new Top 40. Reluctantly replacing my headphones, I settled back down in the pillows – I was an old hand at this now.

A few minutes later I was in theatre. ‘Relax, and count down from ten’ the anaesthetist told me. ‘By the time you get to five, you’ll be asleep.’ I found the idea of knowing the precise point of my departure slightly disturbing, but I did as I was told and began counting. As I did so, I turned to my side and stared at a skull-and-crossbones on a bright yellow bin.

I kept staring. Strange, I thought…I’ve counted down to zero and I appear to still be awake. The room was swimming so I knew something was amiss, but I was clearly still alive. What had happened?

It was only when the surgeon’s friendly face appeared in front of my eyes that I realised: the operation was over. The yellow bin hadn’t been there before – I was in a recuperation zone where I’d been unconscious for hours. It was a very strange experience; of feeling that I was in the past, present and future at the same time. For a few seconds, I thought I was the new Doctor Who. Then I was sick.

The nurses were brilliant on that stay, particularly the one who entertained us by miming along to Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s The Power of Love – I can still see her mouthing ‘Cleaning my soul’ into a bedpan. My wardmates were a Cool Kid who insisted he was going to stay up late and watch Quincy (a request obviously given very short shrift by the nurses) and a boy who cried himself to sleep every night. This time I did feel slightly more like Peter Bowles.

Fast forward a very long time – to a Saturday in January 2014, in fact, and I’m picking up a box at work. Unknown to me, there is a tiny shard of broken glass inside, one with my name on it. I feel a cold sting in my left hand, which becomes a full-on Carrie situation within seconds. With my hand crudely cocooned in kitchen roll, I take a bus to A&E. I sit down in a busy waiting room, where I can’t help noticing that most of my fellow invalids are wearing jodhpurs.

The gash looked very nasty indeed, but once cleaned up it’s rather pathetic – nonetheless I’m given stitches, a tetanus booster and a pamphlet on ‘wound management’. Before I’m sent on my way, the doctor asks if I’ve ever had a cholesterol check.

Oh fuck, I think. This isn’t going to end well. And indeed it doesn’t.

A few days later, I’m in another waiting room, this time for a blood test. A few days after that, I’m called into the surgery and my doctor tells me I have type 2 diabetes. Of course I do. Here are some leaflets you may find helpful, she says: one about your eyes, one about your feet, one about your penis (oh god, not again), one about not eating too much cheese. Oh, and you’ve got to take three pills a day. Three?! Yes, although the upside is that you don’t have to pay for them.

Looking back over all these stories, the ‘Where would I have been without the NHS?’ question is an inevitable one, as chilling as it is banal. Back in 1979, I certainly wasn’t asking who paid for all that fish pie.

Defending the NHS, of course, shouldn’t be a controversial or divisive stance, but it’s increasingly become one. It was depressing, for example, how Danny Boyle’s wonderful NHS tribute at the 2012 Olympics was dismissed by certain people as ‘politically correct’ or an example of ‘virtue signalling’. Yes, they seemed to be saying, we all think the NHS is a good thing, but (to quote Nurse Mills in The Singing Detective) we don’t have to talk about it do we?

That being said, there’s a certain ‘sad piano’ attitude to the NHS that isn’t very helpful either. You hear this sad piano a lot on hospital documentaries (unless it’s one about OCD, in which case they use a ‘funny’ pizzicato harp), and it’s a score that doesn’t really suit the tales I’ve told above. Even on programmes which are notionally about NHS underfunding or mismanagement, the tone is always a depoliticising one, bringing everything back to a world where we wipe our eyes at selfless surgeons and refer to nurses as ‘angels’ with a ‘calling’. This is not only sentimental, it’s disrespectful – these are healthcare professionals dealing with (in all senses) shit, and it’d be nice if a truthful version of their day could be depicted.

A few years ago, when the charcoal wasp (qv) was visiting me a bit too often, I sought the help of therapy and – miraculously – I got it. 12 weeks of CBT, totally free of charge. Not everybody is as fortunate, and I have strong criticisms of the tick-boxy, how-depressed-are-you-on-a-scale-of-one-to-ten way sufferers are assessed for such treatments. But this is a reason to protect the NHS and seek its improvement, rather than an excuse to dismiss it as an untenable 1940s dinosaur.

You see, it’s not really enough to be ‘proud’ of the NHS, or to talk about how ‘lucky’ we are to have it. The words feel appropriate, but they suggest a certain complacency about the service’s immortality; a sense that – like our parents – it’ll always be there. It ignores the fact that we only have an NHS in the first place because people (a) fought hard to set it up, and (b) fight hard in 2017 to keep it standing.

So this Thursday, you know what to do. Don’t let the cunts tear it apart. Let’s ensure that, unlike my granny smith apples and orange squash, things really are shared out fairly.

I’ll leave the closing words to Michael Rosen, whose poem These Are The Hands (written to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the NHS in 2006) are displayed at the entrance to North Middlesex Hospital. It’s a brilliantly unsentimental piece, doffing a cap to hospital staff without patronising them, and rightly acknowledging that most of the work in healthcare is anonymous and unsung. As I attend my annual retinopathy screening, I always try to read it before the eye-drops kick in:

These are the hands

That touch us first

Feel your head

Find the pulse

And make your bed.

These are the hands

That tap your back

Test the skin

Hold your arm

Wheel the bin

Change the bulb

Fix the drip

Pour the jug

Replace your hip.

These are the hands

That fill the bath

Mop the floor

Flick the switch

Soothe the sore

Burn the swabs

Give us a jab

Throw out sharps

Design the lab.

And these are the hands

That stop the leaks

Empty the pan

Wipe the pipes

Carry the can

Clamp the veins

Make the cast

Log the dose

And touch us last.